The Why Behind the Wanderlust

After six months in Rwanda and a week-long sojourn back to the United States, I arrived in Nairobi! Adapting to a new space and new people has, once again, led to questions about what brings to me to East Africa. But, unlike when I first landed in Kigali, I am now prepared with a much better and more concrete answer.

Fourteen months ago, when I decided to spend 2023 working outside of the United States, I possessed little more than an amorphous desire to do something “meaningful.” I was agnostic to place and exact cause – something relating to climate or education or women’s empowerment would be great, and South America or Africa sounded like a good spot to start. When people pressed me on the “why” of my decision, I offered a half-intelligible answer about a desire for a global perspective, and now being as good a time as any – if asked for more specificity, I’d have fumbled to dredge up more cliché.

To my great fortune, I stumbled into a job at Prevail Fund, where we are working to launch and execute billion-dollar initiatives that create sustained change. Our current focus is on increasing foundational literacy for primary school students in Africa and south Asia. On my very first day on the job, David (my boss) brought a booklet that shared photos of students and their testimonials, gifting me a far more compelling “why.”

Recently, I was fortunate to visit a school in Rwanda, offering a direct personal connection to issues that had previously existed to me only on paper. The statistics for global education are appalling. In South Africa, more than four out of five fourth graders cannot read for meaning. In northern Nigeria, more than half of girls do not attend primary schools, despite it being both free and compulsory. The poorest country in the world, Burundi, spends a pitiful $155 per student per year... which is more than double that of the Democratic Republic of Congo ($75). Overall, in the Global South, 9 out of 10 students are failed by the education system. In contrast, in America, 9 out of 10 students succeed due to the education system. But the numbers, depressing as they are, only reflect a certain reality, one that can seem dispiriting and impervious to change.

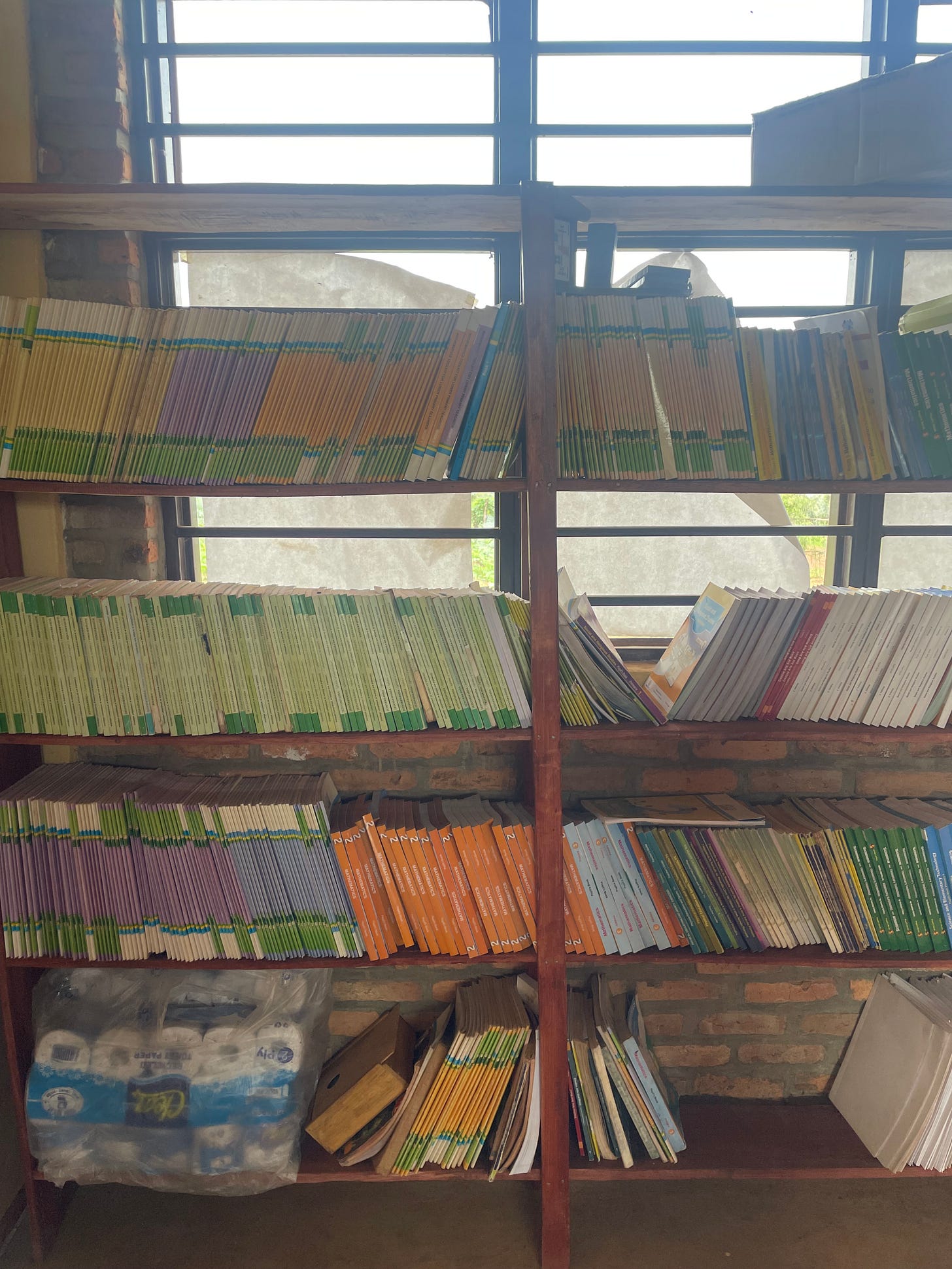

In rural Rwanda, we arrived at an open-air, low-slung building perched atop a steep hill – here was the school. It was a new construction projection, the head teacher told us, and now students only had to walk a maximum of eight kilometers (5 miles) through winding dirt roads and maize fields to get to school. Before, those children might have trekked ten kilometers one way. “A big improvement, it’s much easier for the children today,” he smiled looking at the school. Without doors or windows (much less a computer on sight) but plenty of stray chickens wandering the grounds, at first, I struggled to reconcile this image of education with the brightly-lit classrooms and book-lined shelves of my youth.

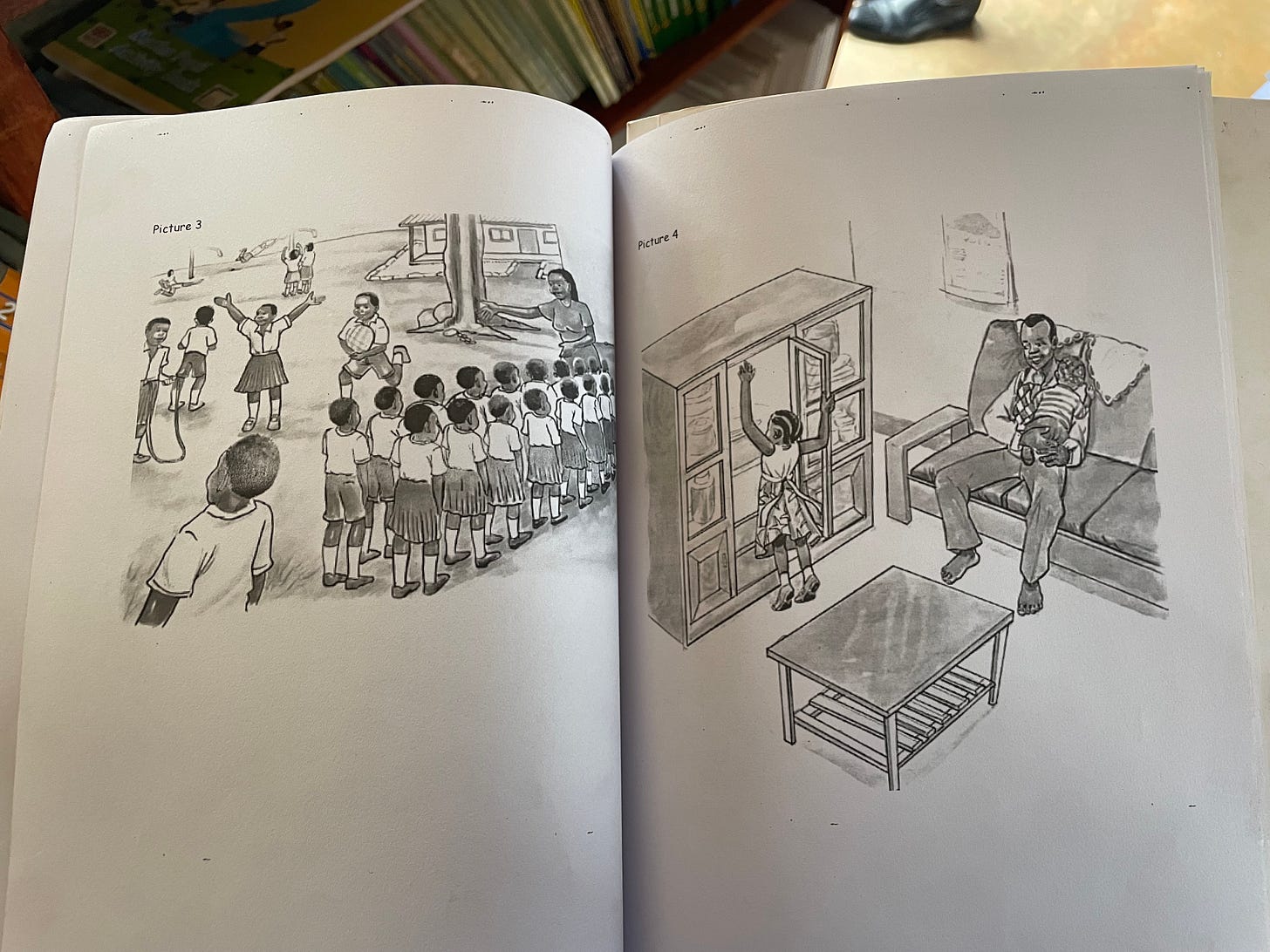

We passed rows of classrooms, where teachers in white coats, resembling doctors, presiding over uniformed students clustered around shared workbooks. (The white coats, resembling those of doctor’s, are standard in East Africa and meant to denote respect, my Ethiopian colleague informed me.) Finally, we arrived at the lesson we were to observe. Upon sneaking into the back of the class, a few curious students stole glances at us strangers, but, for the most parts, the students remained alert and attentive to the teacher.

The class proceeded in an almost call-and-response manner: the teacher would name an object – crocodile, river, grass, mountain – and the students would identify it with their pointer fingers. The teacher might occasionally stop to spell out a word on the board and ask the students to sound it out, letter-by-letter. Then the students would practice writing the word, but without the resources to regularly replace pen and paper, fingers become the default writing utensil as children trace out the shapes of letters on their desks. I recalled that, at my tony private high school, the absence of electronics within classrooms, in favor of old-school pen and paper, was a selling point; in many ways, I had viewed the willful forgoing of electronics as a signal of intellectual superiority and deeper engagement. Now, in that school without a computer in sight, I felt ashamed of my own previous snootiness, so assured I was of access to technology that I had misassigned virtue to its absence.

The children were working on English, the official language of instruction in Rwanda, but Kinyarwanda phrases were sprinkled throughout the lesson to aid understanding. For most of the teachers in Rwanda, English may be their third or even fourth language, and one in which they have no formal education. Just a few years ago, the Rwandan government quite controversially switched all schools to the English language, eschewing Kinyarwanda and severing ties with French, which had previously served as the dominant language. If teaching reading is formidable enough on its own, imagine having to do so in a language that you were never even properly taught; in that light, a difficult task becomes Herculean.

That anecdote – switching languages of instruction with little preparation for teachers – is largely endemic of education policy. Faced with inadequate systems, governments make well-intentioned decisions that ultimately further strain resources, which school officials and teachers attempt to put into practice with limited guidance or incentives. Then, just as the system begins to stabilize, a new government assumes control boasting a sweeping new agenda for policy.

Leaving the school that day, after classroom observations and conversations with teachers and school officials, I was impressed by resilience. Faced in a near-impossible situation, rife with instability and financial insolvency, there were reasons for encouragement. If hope is a survival instinct, then relative perspectives are the tool. An eight-kilometer commute by foot is good, when the alternative is a twenty kilometer one. Teachers learning English outside of school is encouraging, as they are working to equip students with knowledge of which they were deprived. Students in the classrooms is worthy of celebration when a variety of factors – political instability, a worldwide pandemic, planting season – conspire to keep them out of the classroom entirely.

Still, at some point, commendations of resilience are not enough to fix the tragic failing of children throughout educational systems – there must be real changes driven. Politicians use education and schools as campaign rallying cry, mobilizing parents to the voting booths. Education experts and school administrators debate a dollar is best spent on improving the performance of the top students or boosting the prospects of the lowest. And, still, students do not learn.

In theory, we all agree that we want the best for children, but that agreement fragments in practice because, after all, who decides what is best for children? And for which children? These trends are hardly the sole domain of developing countries; the rise of the “parents’ rights” movement in the U.S. speaks directly to those final questions. But, in America, we are essentially seeking to perfect an already pretty good recipe for education, whereas Rwanda and its peers are facing an empty cupboard. This imbalance cuts across so many dimensions: education, trade, healthcare, energy, and more.

We have the resources to address this imbalance in education; in fact, America has enough resources to willfully discards the ones that we have decided that we don’t want. The idea of banning books is infuriating considering the thousands of children who lack access to even a pen, much less a library of full of reading material. We are so far removed from the realities present in Rwanda and elsewhere that we fail to even recognize the privilege inherent in the promise of education that comes as our birthright. The existence of a literate society is a radical and miraculous act because the ability to read is the power to disseminate ideas, form opinions, demand more and better of leaders, and eventually shift social norms. It’s hardly a coincidence that the advent of democracy in America relied on the printing press and that the greatest strides in civil liberties have emerged since the advent of modern public education in the 1840s. The significance of which, when, and by whom words are read cannot be underestimated because reading is the first and, often, only method to borrow another’s ideas, test an understanding of the world, and discover our voice within it. In the end, only a literate world can be an equitable one.

Education has always been a passion of mine, but it’s just one way to ensure that everyone has the ability to thrive – that fundamental human right of opportunity. Other levers are modern medicine, or freedom of speech, or electricity, or a plethora of other luxuries commonplace in the Global North but rare in the Global South. This North-South divide can continue, and we can view international aid – the scraps of our wealth – as sufficient to paper over the inequity. Or we can try to bridge the gap. We can share technical expertise and scientific knowledge more readily; we can support burgeoning human rights movements across the globe; we can focus on solving problems that affect most people, rather than simply debating them and refining convenience for the minority. Now, I can hardly predict the future for myself, and I would not be the first recent college graduate to be accused of a certain idealism. But, at least, I feel like I have begun to carve out a real, tangible “why” for myself, better than what I may have proffered back in January.

"Education is the great engine of personal development. It is through education that the daughter of a peasant can become a doctor, that the son of a mineworker can become the head of the mine, that the child of farm workers can become the president of a great nation. It is what we make out of what we have, not what we are given, that separates one person from another." - Nelson Mandela

I had to take a little time before commenting on your post because you evoked so many emotions in me.

First of all, I am so glad you found Prevail Fund. They seem to be doing great work in an area that is near and dear to my heart. For you to witness firsthand the schools in Rwanda must have been both heartwarming and apalling. It makes me sad to hear how little money is spent on education and how the educational system fails so many children.

Secondly, I can't imagaine a world where I couldn't read. I think that is why I fought so hard against aliteracy here. As Mark Twain so aptly put it, "The man who does not read has no advantage over the man who cannot read." If young students today could understand the privilege they have been given when so much of the world doesn't have the same advantages as many of the people in our country, maybe education would again be held in higher esteem.

Finally, it makes me feel incredibily to proud to know that young adults like you are thinking so deeply about their life and their life choices. It is through people like you that change can happen.